SUMMARY:

-

Alcohol appears to inhibit your brain’s ability to reduce amyloid plaques, which may contribute to a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

-

Your body interprets alcohol intake as a stressful event that may increase inflammation–a leading contributor to Alzheimer’s disease.

When it comes to overconsumption of alcohol, there are numerous well-documented unfavorable effects on your health, both for the short and long term. Too much alcohol can increase inflammation and contribute to brain damage that may lead to cognitive decline and, ultimately, Alzheimer’s disease.

Alcohol, Alzheimer’s, and Amyloid Plaques

A recent study on alcohol and Alzheimer’s revealed that consuming large amounts of alcohol may interfere with your brain’s natural maintenance processes. Dr. Douglas Feinstein, lead study author, and professor at the University of Illinois Chicago College of Medicine suggested that alcohol inhibits the ability of microglia to successfully rid the brain of amyloid plaques—which he believes may contribute to a higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Amyloid plaques are groupings of misfolded proteins that form between nerve cells. The abnormal composition of these proteins is thought to play a critical role in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Amyloid plaques become concentrated first in the areas of the brain that manage memory and other cognitive functions and this is often where evidence of Alzheimer’s disease manifests and can be identified.

“…It might be prudent that if someone is at risk to develop Alzheimer’s, they should consider reducing their [alcohol] intake and certainly avoid binge or heavy drinking,”

Alcohol, Inflammation, and Alzheimer’s

Just last month, the American Cancer Society updated its cancer prevention guidelines and now recommends that “it is best not to drink alcohol.” The problem they’ve identified is that your HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal) axis views alcohol intake as a stressful event. This in turn elevates your stress hormone levels. Chronic exposure to alcohol can quite literally burn out your HPA axis, weaken your body’s response to other stressors, and increase inflammation. Increased inflammation is a hallmark contributor to Alzheimer’s disease.

How do you know if you’re drinking too much alcohol?

Your body has the amazing ability to warn you when you’re taking on more than it can handle. Think about how much harder it is to concentrate when you’ve stayed up all night or how bloated and sick you feel after overeating. Along those same lines, if you find yourself dealing with frequent hangovers, your body is shouting to you that you need to scale back on your alcohol consumption.

Alcohol causes your body to shed water and is a known diuretic. The headache that accompanies a hangover is actually a result of brain shrinkage due to dehydration. Sounds a little scary when put into those terms, huh?

An obvious tip here: If you are trying to avoid Alzheimer’s disease then shrinking your brain is the last thing you want to be doing.

What About Research Showing Benefits of Red Wine?

We’ve all heard that red wine in small amounts can be beneficial for our overall health. For instance, there is research showing that the antioxidants found in red wine may help prevent disease in the coronary artery, a condition known to cause heart attacks that could also contribute to the vascular subtype of Alzheimer’s disease.

However, some physicians and researchers agree that those benefits can be achieved without incurring the risks associated with alcohol. Those antioxidants found in red wine come from red grape skin, so just grab a bag of (organic) grapes next time you’re in the produce section.

Resveratrol is a polyphenol, an antioxidant-like compound found in red grape skin and therefore, red wine. Resveratrol is also available as a nutraceutical supplement in a much higher (and more beneficial) concentration than you can get by drinking red wine.

Final Thoughts

While we do not advocate drinking alcohol in the Brainlift Program, we recognize that there is a body of research showing that light to moderate drinking may have health benefits.

Our recommendation is that you connect with a physician who can help you determine what would be best for you based on your genetics, inflammatory markers, toxic load, gut health, and other individual risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease.

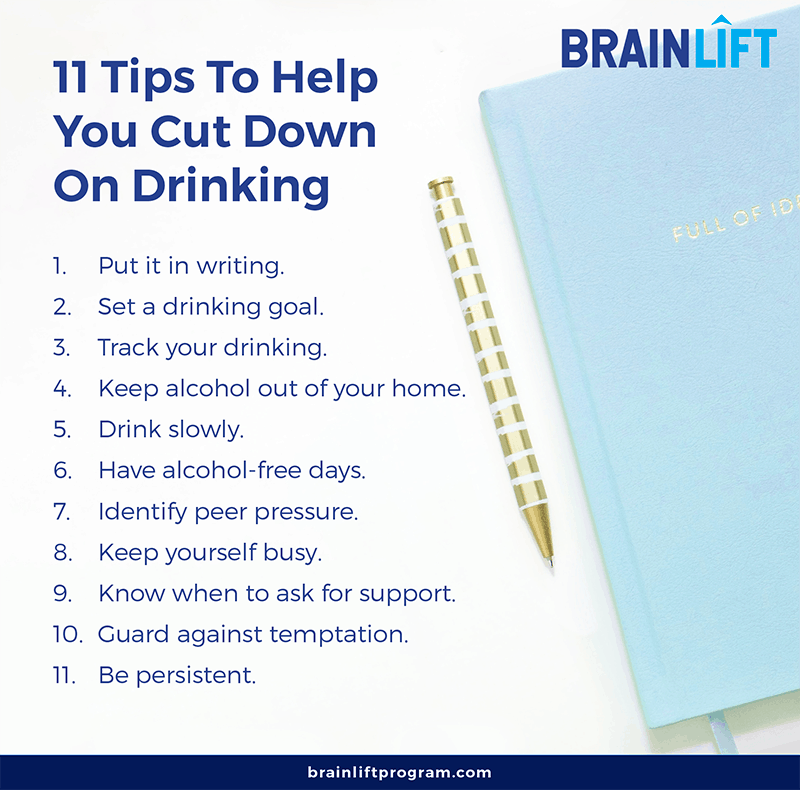

11 Tips to help you cut down on drinking

Do you have room for improvement? If you’re concerned about your brain health, check with your doctor to discuss whether it’s in your best interest to limit or avoid drinking altogether. If your doctor is concerned and recommends that you limit your intake immediately, here are a few suggested steps from Harvard Medical School that you may find helpful:

- Keep it in writing. Make a list of all the reasons why you should limit your drinking — maybe you’re concerned about brain health, sleeping better, or improving your relationships — keep a list of what’s driving this change.

- Set a drinking goal. Limit how much you will drink and how often you drink. Keep your drinking below the recommended guidelines: no more than one standard drink each day for women and for men ages 65 and older, and no more than two standard drinks each day for men under 65. Please note, these limits may be too high for people who have certain medical conditions. Always check with your doctor, they can help you determine what’s right for you.

- Track your drinking. Keep a diary for 3-4 weeks, tracking every time you have a drink. Include how much you drank and where you were. Compare this to your goal. If you’re having a difficult time sticking to your goal, speak with your doctor or another health professional. There’s a lot of free support out there too!

- Keep alcohol out of your home. Making alcohol less accessible is one of the best ways to help limit your drinking.

- Drink slowly. Take small sips of your drink. Drink carbonated juices, water, or coconut water after having an alcoholic beverage. Don’t ever drink on an empty stomach.

- Have alcohol-free days. Start by choosing not to drink 1-2 days each week. You may even be ready to go without alcohol for a week or a month to see how you feel physically and emotionally without it. These types of breaks are a great way to start drinking less.

- Identify peer pressure. Practice ways to say no politely, before you go out with friends or coworkers. Just because others are drinking does not mean you have to, and you shouldn’t feel pressured to accept a drink every time you’re offered. Stay away from those who encourage you to drink.

- Keep yourself busy. Go out for a walk, grab dinner, or catch a movie. When you’re at home, pick up a new hobby, or make time for an old one. Painting, board games, playing a musical instrument, woodworking — these and other activities are great alternatives to drinking.

- Know when to ask for support. Cutting down on your drinking isn’t always easy. Share your goal with friends and family members, and let them know that you need their support. Your doctor, counselor, or therapist are also good people to turn to.

- Guard against temptation. Stay away from people and places that make you want to drink. If you associate drinking with certain events, such as holidays or vacations, create a plan in advance. Take note of your feelings. Try to identify new, healthy ways to cope with stress.

- Be persistent. Most people who successfully cut down or stop drinking altogether do so only after several attempts. You may deal with some setbacks, but don’t let them keep you from reaching your long-term goal. As with any goal, this process usually requires ongoing effort.

-

https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/risk-factors-and-prevention/alcohol#:~:text=Alcohol%20consumption%20in%20excess%20has,or%20other%20forms%20of%20dementia.

-

https://jneuroinflammation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12974-018-1184-7

-

https://chicago.medicine.uic.edu/departments/academic-departments/anesthesiology/research/research-division-organization/neurovascular-and-neuro-critical-care-research-laboratories/feinstein-laboratory/name/douglas-feinstein/

-

https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-are-Amyloid-Plaques.aspx

-

https://jneuroinflammation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12974-018-1184-7

-

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/931995

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10890824/

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842521/

-

https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/11-ways-to-curb-your-drinking

-

https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/7-ways-to-reduce-stress-and-keep-blood-pressure-down

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11830193/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15455646/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11830193/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15455646/